A mirror and a window: The power of arts integration

Rising Up:

A mirror and a window: The power of arts integration, with a classroom view at Pittsburgh Beechwood PreK-5

2021 | Written by Faith Schantz, Report Editor

When Chimene Brant wanted to connect a teaching artist with her students at Pittsburgh Beechwood PreK-5, she contacted Mary Brenholts, director of Artists in Schools & Communities at Pittsburgh Center for Arts and Media. Brant brings artists into her classroom not to perform or exhibit their work, but for “arts integration,” a teaching approach that connects an art form with another subject area to deepen students’ understanding of both. She wanted to center an arts experience around Esperanza Rising, a novel by Pam Munoz Ryan that her 5th graders had read. Brenholts thought Miranda Nichols, a dancer and education outreach intern with PearlArts, would be a good fit. Brant had worked with teaching artists for years, in a school with a history of sponsoring annual 10-week artist residencies for every grade. Though teaching and learning were still taking place virtually, she wasn’t daunted by the prospect of using dance to explore a novel through a screen.

Her students had loved the book, about a Mexican girl forced to emigrate to California during the Great Depression. More than a quarter of the school’s students are Latino and many are from immigrant families. When Brant asked the native speakers in her class to read the Spanish words in the book aloud, “There was pride,” she says. Though it’s set in the past, the themes echoed immigrant stories today.

Nichols came prepared. She’d read the novel and considered how to present key scenes. After talking through which scenes students found important, together they mapped out the sections they would bring to life through movement. Nichols taught stretching routines and basic movements and helped students choreograph a dance as a culminating activity.

Brant says students embraced the project. Twice a week when she told them, “Miranda’s going to be popping in and we’re going to be working with her,” she saw joyful faces. Dancing the story, students made such a deep connection with it that they became Esperanza in those moments, she says. Some saw their own experiences portrayed in the book. Others came away with a better understanding of what their classmates had endured. “Art does that,” Brant says.

The project reflects the way Yael Silk, executive director of the Arts Education Collaborative (AEC), describes culturally relevant arts integration experiences. They can be a mirror for students to see themselves. Or they can be a window on lives that are different from their own.

An issue of equity

Music, visual art, dance, and theater are named as core academic subjects in the federal Every Student Succeeds Act. They are also part of Pennsylvania’s state standards. Schools in the state are supposed to provide students with regular, sequenced instruction that builds skills and develops knowledge about all four art forms. Setting the arts alongside other academic subjects underscores that they have value in and of themselves. Learning in and through the arts also helps students achieve in other subjects, as a body of research has shown.

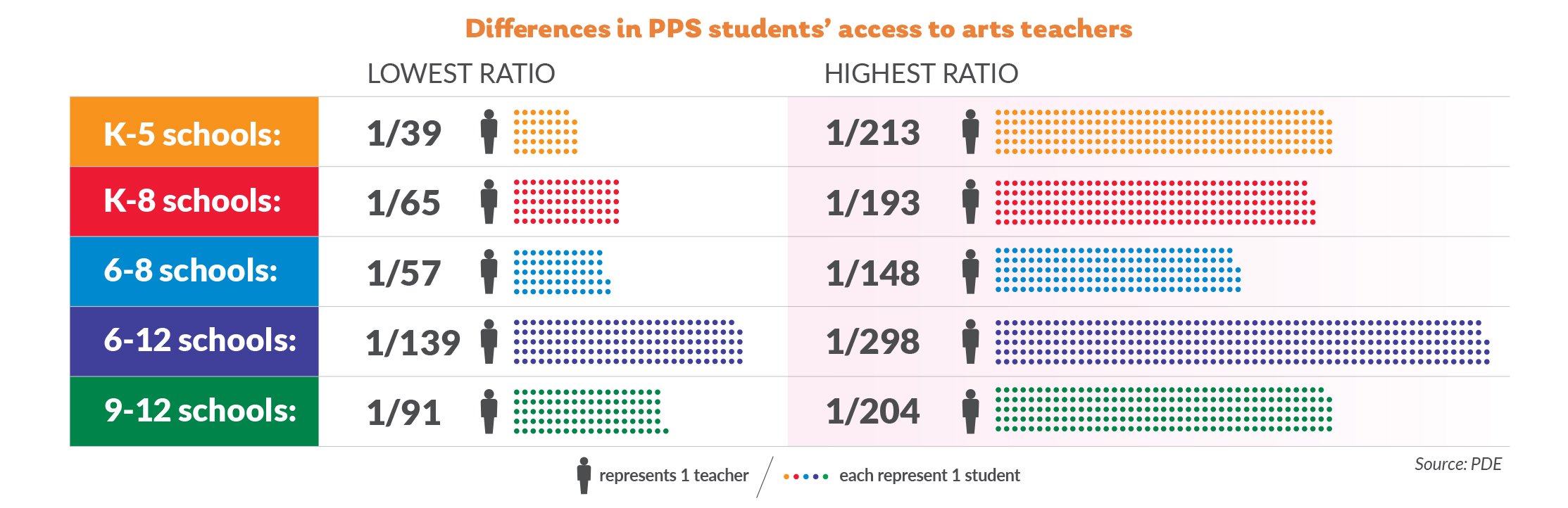

However, across the Pittsburgh district, many students don’t have those learning opportunities. Not only are they missing out on arts integration experiences like the one Brant describes, but they’re also missing the opportunity to take a regular arts class. An analysis of Pennsylvania Department of Education data by A+ Schools appears to show that some PPS students, including in the elementary grades, are not scheduled to take any arts courses during the school year. The ratio of arts teachers to students in a building also fluctuates wildly across the district (see the graphic below).

The graphic shows the ratio of certified arts teachers to students, from greatest access to least access, for each level. Data include full-time and part-time teachers. Pittsburgh CAPA 6-12 was excluded because it offers specialized arts programming.

Silk, a PPS parent, serves on the district’s Arts Advisory Council in her role as executive director of AEC. She says that because the district lacks an arts policy to guide school programming, staffing, and budgeting, those decisions are left to the discretion of principals. “That means that programs are incredibly varied building to building,” she says, raising a clear equity issue. The district has a premier opportunity for deep, sustained arts learning at Pittsburgh CAPA 6-12, its creative and performing arts magnet, which accepts students who audition successfully. Silk points out that students who don’t have a robust K-5 arts experience aren’t likely to be among them. Because schools can do their own thing, “it’s really difficult to understand what is happening building to building.” Lack of information may be one reason many local arts organizations who want to partner with the district have not been able to find a way in.

A new resource for matching arts partners with schools

To address inequities in children’s arts experiences across the region, this fall AEC launched artlook® SWPA. The searchable database and map, based on a model created in Chicago, combines data from schools, arts organizations, and teaching artists. School information can include the number of arts teachers in each discipline and current collaborations with partners, as well as programming needs and interests. For their part, organizations and individual artists can describe who they are, what they offer, and whether it can be customized.

While the Pittsburgh district has yet to fully participate, Silk stresses that artlook is a public resource. In addition to principals, “any teacher, any parent, any student can go on artlook and find a partner that they want to bring to their school, and get connected in that way.”

As more schools and partners join, Silk and her staff expect to see the quantity, quality, and diversity of arts learning opportunities increase. “Diversity” refers to educators’ identities as well as arts disciplines and cultures represented. In a region where the teaching artist population is significantly more diverse than the public school teacher population, she says, schools can use artlook to connect students with educators who look like them. Artlook also gives small and Black-led organizations more visibility. Silk hopes schools will find partners “based on criteria other than, well, these are the folks we know, and the folks we’ve always partnered with.”

Assemble is one of the partners in the artlook database. Located in Garfield, Assemble is a gallery and a “maker space,” with on-site and school programs in arts and technology. Recently, the Assemble team developed an Afrofuturism curriculum, which they brought to the district’s Summer B.O.O.S.T. programs at Pittsburgh Faison K-5 and Pittsburgh Minadeo PreK-5. Executive Director Nina Barbuto says the curriculum involves “looking toward the past to build a new future where we can all see each other, especially making a space for our Black youth to see themselves as people creating and making and thriving in the future.” For example, they have engaged students in writing science fiction—typically a White-dominated genre—featuring non-White characters.

A different learning space

During a recent artist residency project at Pittsburgh Linden PreK-5, 2nd and 4th graders worked with Tina Williams Brewer to create quilts with an emphasis on an African American lens. Photo credit: Nina Unitas

Among the benefits for schools of working with an arts partner, teaching artists have the advantage of coming from outside the closed system of the classroom. They can offer perspectives on content that aren’t bounded by a set curriculum. They can fill gaps in school staff’s expertise. Often, they bring real tools of the trade for students to use. Teaching artists expose children to what the arts are like in professional settings, which can give “a different flavor to the experience,” Silk says. Their identities may challenge a school’s exclusionary culture, which, for the Assemble team, has sometimes led to productive conversations with administrators about how the culture could be improved.

When this breath of real-world air blows into the classroom, it can open up a different learning space. For example, classroom teachers often respond to students’ contributions with evaluative statements (“Good”). Teaching artists change the nature of conversations about students’ work. Creating something with materials, or taking an object apart and putting it back together in a new way, gives children “the opportunity to imagine what they want it to be without the pressure of [being] right or wrong,” Barbuto says. “What you’ve made is what you’ve made. Let’s talk about why you’ve made it.”

Silk adds that teaching artists tend to be “good at seeing young people as artists and treating their work with the same degree of respect as they would their own work or the work of their peers.” They won’t say, “I really liked that” or “You’re so creative.” Instead, they’ll say, “I’m noticing that you chose to emphasize the upper left-hand corner of your drawing by creating some really thick, squiggly lines that are super different than everything else on the page. Can you tell me more about that?” This kind of descriptive, observation-based communication, she says, helps students to feel seen.

Brant views the experience of working with a teaching artist as a kind of apprenticeship for her students. One of the highlights was a quilting project with fiber artist Tina Williams Brewer. Listening to Brewer tell her students, “This is a stitch that they used during the time of the Underground Railroad,” Brant marveled at their opportunity to learn from a nationally renowned artist. At the same time, she doesn’t view it as optional, or a rare special event. As teachers, she says, “We have to do this for our kids.”

Art in tough times

As they always have, the arts also offer the possibility for healing and reconnection. Beyond the individual classroom, Silk hopes the pandemic will force a radical rethinking of education based on what children actually need and deserve, with the arts playing “a huge role.” Not because it’s her job to advocate for the arts, she says, but because one of the reasons people create art is to cope with times like these. Rather than some students taking no arts classes, she asks, “What would it look like if the school day included hours of arts experiences and learning” for everyone?

At Beechwood, just before schools reopened this fall, Brant was thinking about how to set up her classroom for social distancing and which artist she would bring in this year. On her way to school that day, she’d visited a coffee shop that was showing a local artist’s work, and she’d thought about her students. Brant’s father was a metal shop teacher and a sculptor and her mother is a master knitter; art has always been a part of her life. “I stopped,” she says. “I took a moment. I looked at the paintings. I want my kids to do that instead of just passing by.”

Finding an arts partner for your school

Pittsburgh Center for Arts and Media administers, implements, and helps fund artist residency programs in schools, as the regional partner for the PA Council on the Arts. Mary Brenholts, director of Artists in Schools & Communities, will work with administrators, teachers and/or parents to partner one or more artists with a school, for a minimum of a week to a maximum of an entire school year. Residencies are tailored to meet the needs of the school. Typically, a school provides matching funds.

To schedule a virtual meeting, contact Brenholts by leaving a detailed message at 412-606-4723, or by emailing mbrenholts@pfpca.org. View a directory of artists here.Find a partner at artlook® SWPA, and/or talk to your principal about joining this important local resource.

For more information:

AEC’s Activating Arts Learning Theory of Change

For more on the benefits of the arts for academic achievement, see this 2011 report from the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities, and this 2004 report from RAND.

See this article for a discussion of the connection between the arts and social-emotional learning.

Check out the 2021 Report to the Community to see Beechwood’s data on page 49.