Greenfield PreK-8 Reading Achievement

Rising Up:

Greenfield PreK-8: Supporting young readers in a school community

2023 | Written by Faith Schantz, Report Editor

Sharon King knows 4th graders. The 4th grade reading teacher at Pittsburgh Greenfield PreK-8 says her students are “still sweet,” compared to older children. At the same time, “They get sarcasm, which I love,” she says, and there’s less of the “silliness that you sometimes still get in second and third grade.” As thinkers, “an independent voice starts to come out.” They’re caring, and curious, wanting to know everything about their teacher’s life.

Greenfield PreK-8, where King has also served as a reading coach, sits on a tree-covered hill in the Greenfield neighborhood, in Pittsburgh’s East End. Its student population, drawn from the surrounding community, is smaller than the average for district K-8s, with more students who are White and fewer who are economically disadvantaged. The school has a growing population of English Language Learners, including children who speak Arabic, Asian languages, Russian, Spanish, and Swahili. Students who enroll in the school tend to stay.

For reading achievement, Greenfield is an outlier, not only in the district but also in the state. On the PSSA in English Language Arts (ELA), Greenfield students overall typically score higher than state averages for the test. In 6th-8th grades, Black students, students with IEPs, and students who are economically disadvantaged consistently score above district averages—in some cases, at more than double the district’s rate. An A+ Schools analysis of 2017-19 data showed that 86% of Black 3rd graders scored in the Advanced and Proficient ranges, much higher than similar students in the district and the state. At least half of White 3rd graders score in the Advanced range year after year.

These numbers don’t mean that teaching 4th grade reading at Greenfield is a breeze. As in every other school, King’s students come into the classroom with a variety of learning needs. Some need to be challenged with above grade-level content. Some have disabilities. While King says the primary grades teachers work very hard on “foundational skills,” some 4th graders still struggle to sound out words, while others pronounce words correctly without knowing what they mean. Some are learning to read English in addition to another language. And—as in every other reading classroom—each child comes to class as an individual reader, with preferences for what they read, how they read, and how they share what they’ve learned from text.

Teaching children to read is arguably the most important job of any elementary or K-8 school. Here, we look at how one community supports its young readers in the classroom and beyond, and how the district plans to raise reading achievement for all.

In 4th grade, the focus is on comprehension, but what does it actually mean to “comprehend” what you’ve read? And how does a teacher move students from sounding out words on a page to learning from those words, and using that knowledge to create something new? For King, it involves activities that promote a deep engagement with words combined with an approach to teaching that puts students at the center.

In her reading classes last year, King established “very clear rituals and routines, very clear ways that we work throughout the day, so the kids are very comfortable with what’s coming.” She began each three-period block with a PowerPoint that outlined the agenda and the goals for the day, illustrated with pictures and examples. For the students who still needed practice in decoding words, she usually began the lesson with exercises to strengthen foundational skills. From there the class moved to the study of word patterns to help students understand their structure—Greek and Latin roots, prefixes and suffixes—as well as words with related meanings, such as synonyms and antonyms.

After a grammar activity, they read and discussed a story or a nonfiction work. Finally, students turned to the essays, informational texts, or stories they were writing themselves. To help them make their writing more effective, King encouraged them to use the material they had just read as a “mentor text.” For example, when students were writing short stories, they read the novel Lunch Money, by Andrew Clements, about a boy who sells his homemade comics at school. They combed through the book to find “vivid verbs” with an eye toward using them in their own stories.

A key concept from learning research is that deep learning can occur when we connect new information to what we already know. Isolated facts or concepts—such as vocabulary words students memorize for a test without ever using—are likely to be forgotten. To help students make more than superficial connections to what they were learning, King layered in related content that she knew would engage them. Before they read Lunch Money, they studied comic books as a genre, leading some to turn the stories they were writing into comics. Next, they worked with a partner to come up with products they might sell at school, as the main character does in the book. Students made posters to advertise the items, and “they were so excited, they actually started to produce the products,” King says. “It really got them thinking and got them being extremely creative. And they could connect to the main characters differently than…let’s open the book and let’s just start.”

Her approach to teaching vocabulary was similar. It wasn’t “one day we did vocabulary and then we’re never going to use those words again.” After examining a word’s structure (such as how profit is related to profitable), students became “vocabulary detectives.” She told them, “Now we’re on a hunt for the word. We have to see how the author uses it in context.” Profit, for example, can be a noun or a verb. In their reading notebooks, students created illustrated vocabulary charts. They played computer games based on the words and incorporated them into their own writing. “The whole point is that it carries over into their learning,” King says.

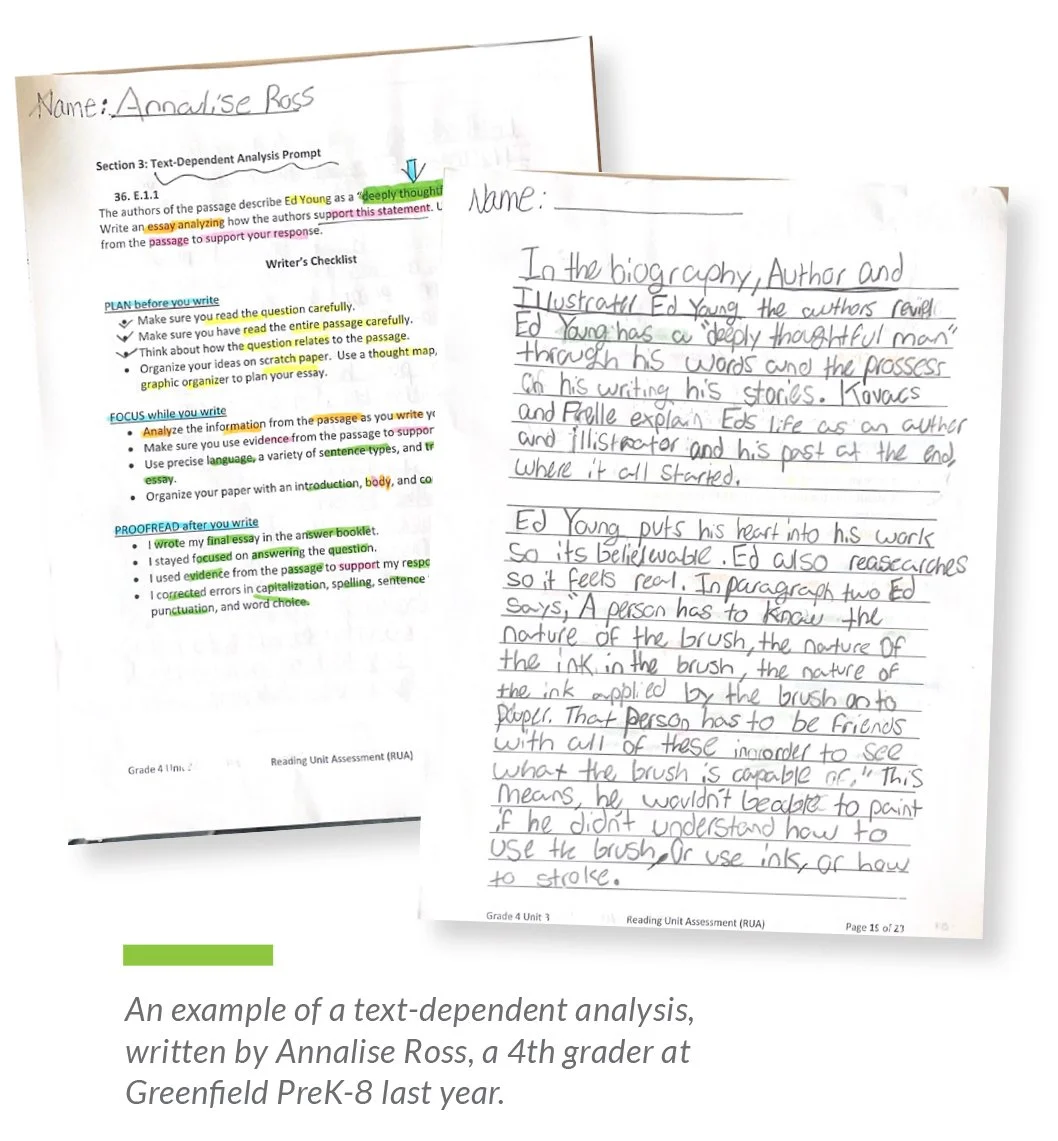

One of the biggest shifts she sees between 3rd and 4th grade is in the amount of writing, and the forms of writing, students are expected to do. Writing is a skill of its own, but it’s also a way to coax meaning from a text, and to show that the writer understood what they read. To meet Pennsylvania’s core standards for ELA, King’s students must write what’s known as a “text-dependent analysis,” which is tested for the first time on the 4th grade PSSA.

For the test, students read a passage and write to a prompt that asks them not only to show understanding, King says, but also to refer to evidence from the text and analyze what it means. She describes the process as “really pulling meaning into what a text offers.” And, she adds, “It’s a very difficult skill.” To help develop their analytical writing skills, she offered plenty of opportunities for students to write and revise their work, sometimes editing with them one-on-one. She also taught them critical reading strategies, including highlighting important information, “annotating” the text to note main ideas and inferences, and looking back through it for answers to how, what, and why questions.

Teaching each child

King has been with the district for almost 25 years, teaching several grade levels and working as a reading coach. Still, she doesn’t attribute her success as a teacher to her experience or to her subject-matter expertise. Rather, it’s in the quality of the relationships she builds with her students each year. “I know their families,” she says. “I know their sibling’s name, I know their interests. I take time to get to know each one of them on a very personal level so that each one of them feels special and not ignored.” Maintaining those relationships involves a daily practice of checking in with each student. If a child comes into class hanging their head, she’ll ask if they want to talk, maybe stay in the classroom with her at lunchtime.

Her efforts have paid off not only in students’ well-being, but also academically. Children who feel that their teacher knows and cares about them are more likely to participate in discussions, she says—and studies have shown that talking with others about a text is one of the main ways students develop comprehension strategies. Because they have a sense of belonging, King doesn’t need to spend much time on classroom management, leaving more time for instruction. She says, “They’re going to put everything into what they do because of the relationship that they have with me and how they feel.”

For students in the class who are racial minorities and/or English Language Learners, she finds opportunities to represent aspects of their cultures, which benefits all students. “If I know a child has more to offer, [I’ll ask], ‘Would you like to share about your family?’” she says. For example, during a unit on natural disasters, students from South America talked about their experiences with earthquakes, bringing the topic to life for their classmates.

Enrichment for all

The unit on natural disasters was so popular with students that King added activities and a culminating project. Along with informational texts, they read a novel about the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and studied the phenomenon of underwater volcanoes in Hawaii. Beyond the science and the drama, the topic sparked their compassion, and inspired their developing social consciousness. They discussed the humanitarian response to actual disasters and drew up plans for their own community to use if such an event happened here. “I couldn’t believe how engaged the kids were,” King says. “They would bring in their own books, and they would create extra things and present those to one another.” For the culminating project, they worked in groups to create and present their learning in their choices of format, including dioramas, posters, or PowerPoints.

King viewed it as enrichment for the entire class. “Some of my struggling readers excel in projects like this. Some of them have amazing visual art skills that come to life, or they just have a different perspective of interpreting what we’ve learned.” She believes all children deserve such opportunities. “I see the light in their eyes when they know they can do something that’s different and special, and it shouldn’t come down to an IQ—ever—that allows that child to have that experience.”

One of King’s students was Annalise Ross, a 5th grader at Greenfield this year. Annalise doesn’t remember how she learned to read, only that she got serious about it in 3rd grade when she started reading books with chapters. Now, reading is her favorite class at school and a favorite activity at home. With a parent and her younger sister Aurelia, she visits the Squirrel Hill branch of the Carnegie Library “every time we finish the whole bunch of books we get,” usually within a couple of weeks. Each night, she says, “Our parents read to us, and then we get to read our own books in our beds.” Recently as a family, they read novels from the Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan, books Annalise had already read but enjoyed revisiting with Aurelia. On her own, Annalise reads novels about mythical creatures, such as the Wings of Fire dragon fantasy series by Tui Sutherland, and fiction and nonfiction about Greek mythology. She channeled that interest into a short story she wrote for King’s class about demigods whose powers mysteriously weaken.

At school, Annalise found the assigned texts engaging. “Ms. King always makes it fun to read the stories, and the stories are interesting, too,” she says. She also responded well to the way King structured the class, especially the daily partner and small group work. “I like working with people,” she says, “because then I can hear different ideas.” Annalise feels she learns the most when she’s taking in something new. After that she explores the new content by “reading about it and then thinking about it and thinking through it with maybe a partner or friend.”

For her, the best part was pulling together her learning into a presentation of some kind. Annalise loves projects so much that when schools closed due to the pandemic, her biggest regret was not being able to finish the habitat project she had started—an assignment, she notes with a hint of sibling rivalry, that Aurelia was able to complete. By the end of the year in King’s class, however, Annalise had created a “bunch” of PowerPoints, she says.

Another student in one of King’s classes last year was Evan Gaviola. Her mother, Jocelyn Gaviola, says Evan picked up reading very quickly, possibly because she had a strong preschool teacher. Gaviola’s son Isaac began kindergarten at Greenfield in the fall of 2020, from home. Prior to that year, she says, “I would have thought it was impossible to learn how to read over the Internet remotely.” (At the time, King was a reading coach; she recalls that teaching phonics and phonemic awareness through a screen was “extremely challenging.”) Nevertheless, Gaviola says Isaac’s teacher, Melanie Barnes, “was incredible at knowing what level the kids were at and what they needed to get to that next level, all virtually.” Barnes brought Isaac from “understanding phonics and letters and sounds to fully being able to read in that year.” She adds, “I’ve heard that feedback from lots of parents.”

At home, she says, “We’ve always been family readers where we’ll all read together, we’ll read out loud together, or we all take time at the end of the day to sit together and read our books independently.” Like the Ross family, the Gaviolas are frequent users of the Squirrel Hill library. Evan likes mysteries and series where she can dive in and “stay in that world for a little while,” Gaviola says. Isaac, now in 3rd grade, likes books about animals and historical events, and graphic novels such as the Dog Man series by Dav Pilkey. Often, his mom hears him laughing in his room, rereading a book and enjoying the funny parts all over again.

As their reading skills developed, Gaviola and her husband Nick paid attention to teachers’ comments on schoolwork that came home, and counted on their children to alert them if they were struggling. But even with the amount of reading they do at home, she says, “I think for any parent it’s hard to know what’s normal…. So I really depend on the teacher’s feedback.” During the pandemic, the district launched the TalkingPoints platform for parent/teacher communication; Gaviola used it to share information about her children, check on homework assignments, and raise social-emotional issues among students that came to her attention. Since buildings have re-opened, she says, teachers once again stand outside during dismissal. “I often see parents approaching them at that time and just having those quick conversations about how the students are doing, about things that are expected. So I really feel [teachers] are members of the community. It feels like they’re all available to us.”

With Evan in particular, teachers have gone beyond ensuring she could read. Last year, Evan spent some lunchtimes with King to talk about books she loved. With her 3rd grade teacher, she discussed starting a summer book club. Teachers have “bent to her” as a reader, Gaviola says, knowing the type of books she prefers, and continuing to recommend titles even after she left their classrooms. This kind of attention has contributed to “a very high level of reading comprehension” on her daughter’s part, she says.

Most district schools have not seen anything like Greenfield’s success in reading (see the graphs below). Dr. Jala Olds-Pearson, now in her second year as the district’s chief academic officer, says that roughly 60% of students are not reading on grade level, and “no parent would deem that acceptable” for their child. She notes that primary grade teachers have been reporting for awhile that they didn’t have enough time to teach the foundational skills. Community advocates, including A+ Schools, have sounded alarms for years about the number of children in the district’s schools who can’t read proficiently. The early years are crucial. Students who are still struggling to read by the end of 3rd grade are likely to fare poorly in all subjects that depend on reading, and are four times more likely to drop out of school.

Last winter, the district adopted a new reading curriculum for K-5, McGraw Hill’s Open Court, and teachers began using it this fall. The district has changed up its reading curriculum in the past without seeing lasting improvement. But this time may be different.

Pittsburgh has joined a wave of other districts that are trying to better align reading instruction with research, in particular, research on the brain. Brain studies have shown that we aren’t “hardwired” to read the way we are hardwired to speak, as was previously thought. Instead, in order to read and comprehend a word, our brains must learn to link the pronunciation with the letters and the meaning.

Though this research has been around for decades, in many classrooms techniques based on the belief that reading is a “natural” process have lingered. For example, some teachers were taught to encourage children to guess an unfamiliar word based on a picture or the context instead of sounding it out—skipping the crucial step that trains the brain to link the letters with the sounds. With the evidence-based approach, Olds-Pearson says, “We have to make sure that [students] understand what they’re doing, that they understand how to form words, that they actually understand the rules, and it’s not something that they’re going to guess at.”

Along with different ways of teaching foundational skills, Olds-Pearson says Open Court offers tools to help teachers organize small group instruction on specific skills, and better ways to identify the sources of reading problems. Schools will continue to use existing intervention programs, such as Reading Horizons, but those programs will be reviewed this year to determine their effectiveness.

What about the students in grades 6-12 who were not served well by previous methods? Olds-Pearson says the district is offering teachers professional learning sessions that include information about the science-based approach. For those grade levels, the district has also adopted a set of contemporary novels and works of nonfiction to better engage students, including Born a Crime by Trevor Noah, The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, and Pinned by Pittsburgh author Sharon Flake.

Olds-Pearson hopes that focusing on more active learning in general will boost students’ reading achievement at all grade levels. Along with using more relevant materials, this means teachers posing more questions that ask students to think, she says, and “making sure that [students] are demonstrating understanding as opposed to compliance.”

She adds, “All of the research clearly shows that with a laser sharp focus on practices that have been proven to work, we can get there.”

Just before school ended last year, Sharon King downloaded the new curriculum units and started to explore them. She planned to meet during the summer with 4th grade teacher friends from across the district to study Open Court, and with the 5th and 3rd grade teachers from Greenfield to discuss the individual students she would be sending on and receiving.

She would not have that year’s 4th graders in class again, but she wasn’t letting go of them just yet as readers and writers. She met with a group of parents who had requested hands-on activities to keep their children learning. She sent home a list of books for summer reading. And as a parting gift, she gave each child a blank book, and challenged them to create a story they could read to her new 4th graders in the fall.

Apparently a year of exploring mentor texts, being vocabulary detectives, creating PowerPoints, and reading compelling stories had only whetted their appetites. Within days, a few children had emailed their works-in-progress.

“I said, ‘Give me some time to give you some feedback.’ And they’re like, ‘Mrs. King, I’m already on chapter three.’”