Sunnyside PreK-8 8th Grade Algebra

Rising Up:

Pittsburgh Sunnyside PreK-8: Eighth grade algebra—What does it take?

2023 | Written by Faith Schantz, Report Editor

Eric Rogalsky looked out at his Eighth Grade Math class, and he saw a bright student who was bored. Rogalsky has taught math for 22 years at Pittsburgh Sunnyside PreK-8, located in Stanton Heights just over the border with Morningside. Depending on the year, he may teach 6th, 7th, and 8th grades, so he gets to know his students pretty well. But this student had transferred into Sunnyside from another Pittsburgh public school.

Rogalsky ran into the math teacher from that school at a district professional development session. “I got one of your former students,” he said, naming the girl. He mentioned that he was thinking of switching her into his algebra class. The other teacher demurred. He didn’t think she had the “right stuff” to take algebra as an 8th grader, he told Rogalsky. She wasn’t mature enough. She wasn’t motivated. “She’s not this, not that. And I just looked at him and I said, ‘That’s not the feeling I get…so the change of scenery must have sparked something in her,’” Rogalsky recalls.

This student illustrates one of the dilemmas schools and districts face when they offer 8th grade algebra. If it’s not standard for all 8th graders, the questions arise: who should take the class, and how should that be determined? On the one hand, teachers may be best positioned to know when students are ready. On the other hand, teachers are human, with biases and blind spots that may get in the way of accurately assessing a student’s ability and motivation.

Nationally, the question of who gets to take algebra in 8th grade is fraught. Research has shown that students of color are less likely than White students to be offered the class, even when their math achievement is similar. These data have led some advocates for greater equity to recommend that districts use more objective measures, such as test scores, and fewer subjective methods, such as teachers’ recommendations, to open up algebra classrooms to more Black and Latino 8th graders. Other advocates for equity, however, have encouraged districts to delay algebra until 9th grade so teachers can focus on better preparing all students to pass the course.

Among educators and researchers, there is more agreement about the benefits of algebra for 8th graders. Those students have more room in their high school schedules for advanced math. And students who take math beyond Algebra 2 are much more likely to go to college and graduate. Students on this path may be able to enroll in college courses while they’re in high school, reducing their future college debt. Taking algebra in the middle grades is especially important for students who are interested in STEM fields, which arguably can lead to some of the most interesting, varied, and highest paying careers.

Algebra taking and school size

In Pittsburgh, Chief Academic Officer Jala Olds-Pearson says the goal is to increase the numbers of students who are ready for algebra in middle school. Currently, however, qualifying for the course doesn’t necessarily mean students can take it.

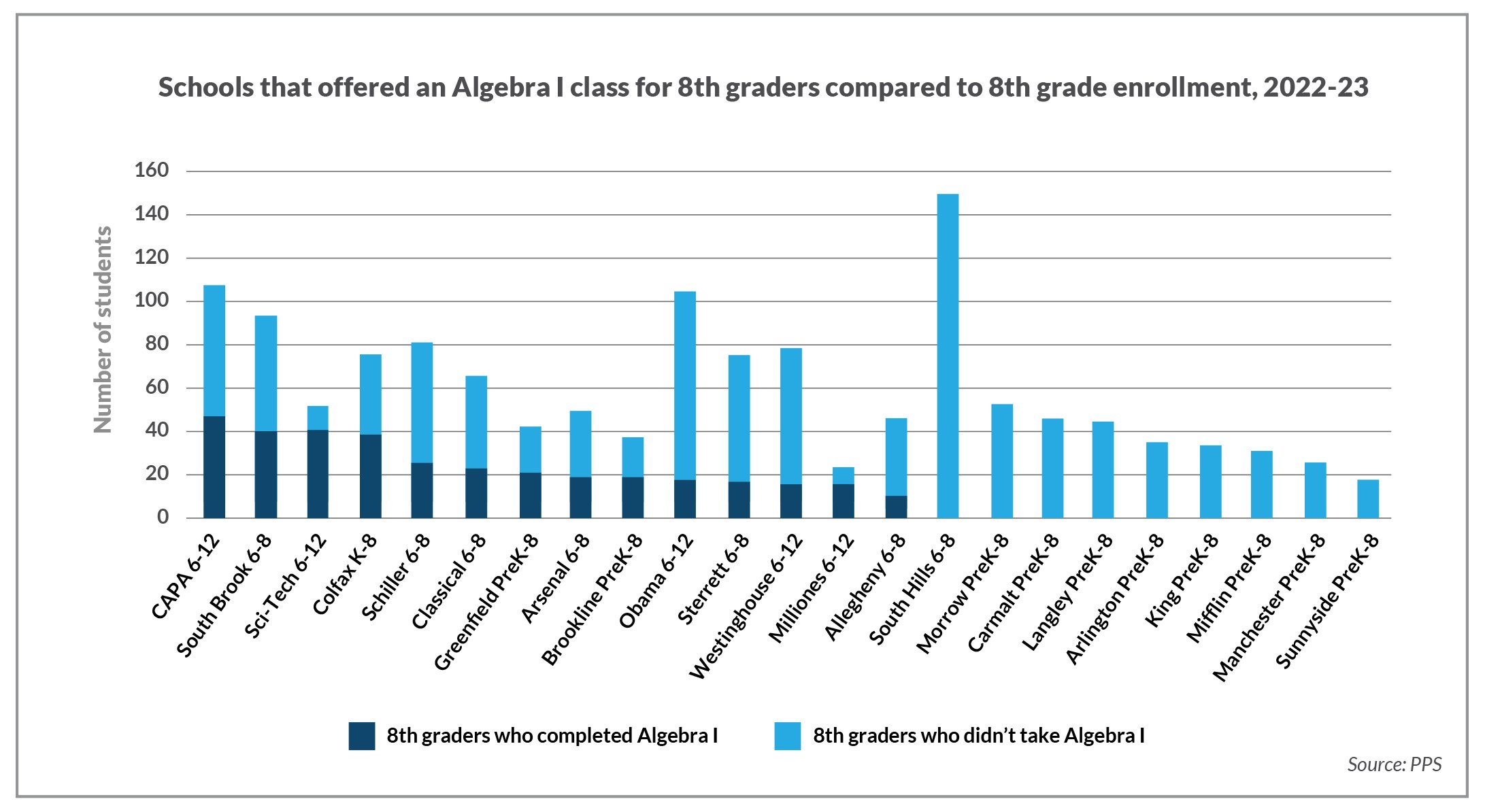

The graph below shows the number of students who took Algebra I at their school in 2022-23 compared to the size of the overall 8th grade class, for all schools in the district with grades 6-8. Fourteen out of 23 schools provided an algebra class for qualifying students. The graph shows that all but two of the schools with an algebra class had 8th grade enrollments of 40 or more students. The average number of 8th graders in those schools was 73.

Sunnyside is one of a small number of district K-8 schools that have consistently offered algebra. But last year, that changed.

In the spring of 2022, Sunnyside’s 7th graders took the NWEA-MAP test in math, a computer-based test that automatically assigns scores to one of the score ranges on the PSSA, Rogalsky says. Based on those scores, only a few students qualified for 8th grade algebra. Rogalsky contacted Jessica Kapsha, coordinator for 6-8 Mathematics. “I have so few kids,” he said. “Is there anything else that I could do to see if I have other students that are ready?”

He and Kapsha identified another test he could give his students. Still, only three met the cut-off score. The school had two 6th grades, one 7th grade, and one 8th grade that year. The only other teacher certified to teach math in the upper grades was already teaching a full schedule of reading. Given the constraints, Rogalsky says, “The principal could not feasibly say, ‘I’m taking these three students and letting you teach them for 90 minutes, five days a week.’”

Sunnyside’s situation wasn’t unique. Rogalsky heard from Kapsha that “there were other schools that were in the same predicament as me, where there were not enough students, so they weren’t going to offer it, and they had normally offered algebra” in prior years.

This fall, the numbers at Sunnyside were similar. “We do not have, one, enough staff, or two, enough students” to offer an algebra class, Rogalsky says. Five or six would have been eligible, he believes.

In the classroom

Eighth Grade Math, based on the Go Math! curriculum, is a broad course that includes content from algebra and geometry. Among other topics, students learn about scientific notation (a way of representing very large or very small numbers), transformational geometry (using mathematical methods to turn, slide, or flip figures), and ways to measure the slope of a line, Rogalsky says.

In Algebra I, based on the McDougal Littell curriculum, topics include factoring (simplifying an algebraic expression by finding the common factors), operations with binomials (algebraic expressions that have two terms, such as x + 1), and working with different types of equations. Because topics other than algebra, such as transformational geometry, are tested on the PSSA, he adds them to the algebra class, making it even more of a challenge, Rogalsky says. (Students who take Algebra I in 8th grade are required to take the Keystone Algebra Exam as well as the PSSA in math.)

He structures both classes similarly and uses the same teaching approach. Each begins with a “warm-up” activity, followed by discussion. If he’s introducing a new topic, they explore it through a sample problem, “and then I give notes as if they were in high school already,” he says. After that, they look through the examples in the book together, followed by guided or independent practice in solving problems and answering questions, sometimes working together in small groups. Each class also has a computer component, with “intelligent” software that provides assignments that progress in difficulty, individualized feedback, videos, and examples. Rogalsky also “differentiates” by giving students worksheets that have the same problems with varying levels of support.

“There are days where the topic goes remarkably well and perfect…. Everything clicks, everything is in place, all the students understand, everything works right. And I can move through the whole lesson in 90 minutes,” he says. Since few days are like that, as a teacher “you’re always monitoring and adjusting your lesson.” He extends that same flexibility to his students. “I try and make my class as interactive as possible and as friendly as possible, where it’s a safe space” to take risks and make mistakes.

Last year, for the students who would have taken algebra if the school had been able to offer it, Rogalsky assigned higher-level problems. Once they had completed their work, “I almost challenged them to be the teacher,” he says. He has always told students that there is more than one path to a solution; it follows that there’s more than one way to explain the math involved. He directed his young assistants toward classmates who needed help. “They’re not getting what I’m saying,” he told them. “Do you think you could help them out and explain to them a different way?”

Teaching algebra calls for another kind of communication skill: the ability to persuade students that they do belong in the class. Students usually qualify through a mix of test scores, report card grades, Rogalsky’s professional opinion, input from other teachers, and the principal’s sign-off, but some begin the course fearing they won’t succeed. Some were accepted even though they didn’t meet the test score cut-off. Some have disabilities. Some may doubt themselves because of ideas about who can be a “math person.” Historically, Rogalsky says, the class has been balanced by gender, and has generally reflected the racial make-up of the school’s enrollment, which was 48% Black and 38% White, with smaller percentages of Multi-ethnic, Hispanic, and Asian students last year. Studies have shown that the math achievement of girls and Black and Brown students in particular may be negatively affected by stereotypes of what a good math student looks like and what others might expect them to be able to do.

To support students whose confidence wavers for any reason, Rogalsky has a simple technique. “Instead of standing over them, I’ll sit down next to them to show them that I have an interest in what they’re doing, and I care about what they’re doing…and [I’m] treating them with the respect that they deserve.” Daily check-ins—“How are you doing? Is everything going all right?”—serve the same purpose. He also shows students their own growth progression. “I’ll compare their work from seventh grade to eighth grade. I’ll give them examples and say, ‘Look, this is what you did. This is what led me to believe what you can do.’… And then I pull out the old, ‘I told you you could do that,’” he says.

At times he’s had students who were excited to take the class at first, “but then when it got down to the nuts and bolts of it, they kind of shrunk down and were like, ‘Well, I’m just going to do enough to get by,’” he says. “I try not to let them do that.”

The future of 8th grade algebra

Back in the early 2000s, Rogalsky was the one who pressed for the school to offer its first algebra class. He had “a spectacular group of students” who needed to be challenged, and he told the principal, “I will take whatever professional development I need to do to get ready. I will do whatever it takes.” Now, however, he doesn’t think the district’s goal should be to get more 8th graders into an algebra class at this time.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, some of his students are two years behind grade level, he says. When school buildings closed, this year’s 7th graders were in 3rd grade, when they’re taught multiplication and division, the foundation for other areas of math. He has tried to find creative ways to address the content students missed due to the difficulty of teaching and learning math through a screen. But he believes moving too quickly can backfire. “Sometimes you’re going to break a student if you push them too hard,” he says. “They just give up, they get frustrated, and then you’ve almost lost that student…. If you want us to teach our best, that’s fine. If you want the students to learn their best, you can’t expect to push them at a rate that they’re not ready for.”

While getting more 8th graders into algebra is the district’s goal, Olds-Pearson says she and the math department have been spending “a tremendous amount of time” looking at earlier grade levels, in order to pinpoint where students’ math achievement appears to break down. Based on low math scores on the 3rd grade PSSA (the first tested grade level), they are focusing on grades K, 1, and 2, she says.

Declining enrollment may mean that more 8th graders who are ready for algebra won’t be able to take the course in the future, as individual school populations decrease. For example, Sunnyside’s enrollment dropped from 345 students in the 2013-14 school year to 234 in 2022-23. In those situations, Olds-Pearson says, “We’ve provided different opportunities for kids to take classes in other schools.” A few Pittsburgh South Hills 6-8 students took algebra at Pittsburgh Brashear High School last year. “But it really is tough. It’s a case-by-case basis because there’s a lot of factors involved in terms of the options.” For now, “our [eighth grade] Algebra I classes…live in school spaces where we have a good number of students who are ready.”

For the girl who transferred into Sunnyside in 8th grade, there was a happy ending. Rogalsky bypassed the other teacher’s concerns and asked her to consider moving to his algebra class. At first, she hesitated. She asked him if he was sure. “And I said, ‘I’m looking at your work. I see the way your ability is going. I see how you react to new topics.’” She joined the class, and “it was like the lights turned on. She was happy. She was engaged. She was one of my better students,” he says.